Blog

Perspiration

I originally considered blogging about the progress of BASIC-DOS on a daily basis, but I quickly dismissed that idea, because like most programmers, I’d much rather be writing code than documenting it, and no one would really be that interested anyway. The GitHub repository has all the gory details for anyone who really cares.

But, with the target release date only 8 months away now, an update is long overdue.

The Boot Sector

This is where development started. And I’m happy to report that the boot sector is in good shape. It includes features that I don’t think existed in any version of DOS until MS-DOS 5.0:

- IBMBIO.COM and IBMDOS.COM boot files can be anywhere in the root directory

- The boot files can use any clusters (they don’t need to be contiguous)

In addition, the boot sector will prompt you if a hard disk is detected, and if you press the Esc key, you can boot from the hard disk instead of the BASIC-DOS diskette.

System Configuration (CONFIG.SYS)

The BASIC-DOS boot code also loads CONFIG.SYS into memory, so that the system can be tailored to your needs. PC DOS didn’t support CONFIG.SYS until version 2.0, over 1.5 years after the IBM PC and PC DOS were introduced.

Installable device drivers (using the DEVICE keyword) aren’t supported yet, but support does exist for the following configuration options:

- BOOTKEY (eg, BOOTKEY=D to simulate pressing ‘D’ at the boot prompt)

- CONSOLE (eg, CONSOLE=CON:40,25,0,0,1 to create a 40-column console)

- DEBUG (eg, DEBUG=COM1:9600,N,8,1 to enable debug messages to COM1)

- FILES (eg, FILES=20 to allocate memory for up to 20 files)

- MEMSIZE (eg, MEMSIZE=32 to limit system memory usage to 32K)

- REM (for remarks – although any unrecognized line will be ignored, too)

- SESSIONS (eg, SESSIONS=4 to allocate memory for up to 4 sessions)

- SHELL (eg, SHELL=COMMAND.COM AUTOEXEC.BAT)

- SWITCHAR (eg, SWITCHAR=- if you’d rather type “DATE -P” instead of “DATE /P”)

Sessions are one of the cool new features of BASIC-DOS. More on that below, when I talk about the CONSOLE driver.

Built-in Device Drivers (IBMBIO.COM)

IBMBIO.COM is the first file loaded by the boot sector, and it’s little more than the concatenation of all the standard (built-in) device drivers, followed by a small bit code to call each driver’s INIT function. If a driver reports that it isn’t needed (eg, if no serial or parallel adapter is present), then the driver is discarded.

If you type the MEM /D command, you’ll see that BASIC-DOS has most of the

usual built-in DOS device drivers, although the only ones that really do

much at this point are:

- CON (combined screen and keyboard driver)

- COM1, COM2, etc.

- CLOCK$

- FDC$ (yes, BASIC-DOS block drivers can have names, too)

- PIPE$ (ie, a true pipe device)

BASIC-DOS device drivers are very similar to DOS drivers. For example, they use similar header and request packet structures. But there are also some significant differences. For example, PC DOS drivers never fulfilled the promise of asynchronous I/O, even though they were designed with separate STRATEGY and INTERRUPT entry points. All I/O was synchronous, and in general, input devices were polled.

In BASIC-DOS, support for asynchronous I/O is baked in. Drivers have a unified REQUEST entry point that doesn’t need to preserve any registers, and both the BASIC-DOS CON and COM drivers support interrupt-driven I/O.

The Console Driver (CON)

The Console (“CON”) driver is a cornerstone of SESSIONS, one of the major features of BASIC-DOS.

BASIC-DOS supports a default of 4 sessions (which you can change with the SESSIONS keyword in CONFIG.SYS), and each session can be configured to use a specific portion of the screen and a specific shell. For example, the following pairs of lines in CONFIG.SYS:

CONSOLE=CON:40,25,0,0,1

SHELL=COMMAND.COM

and:

CONSOLE=CON:40,25,40,0,1

SHELL=COMMAND.COM

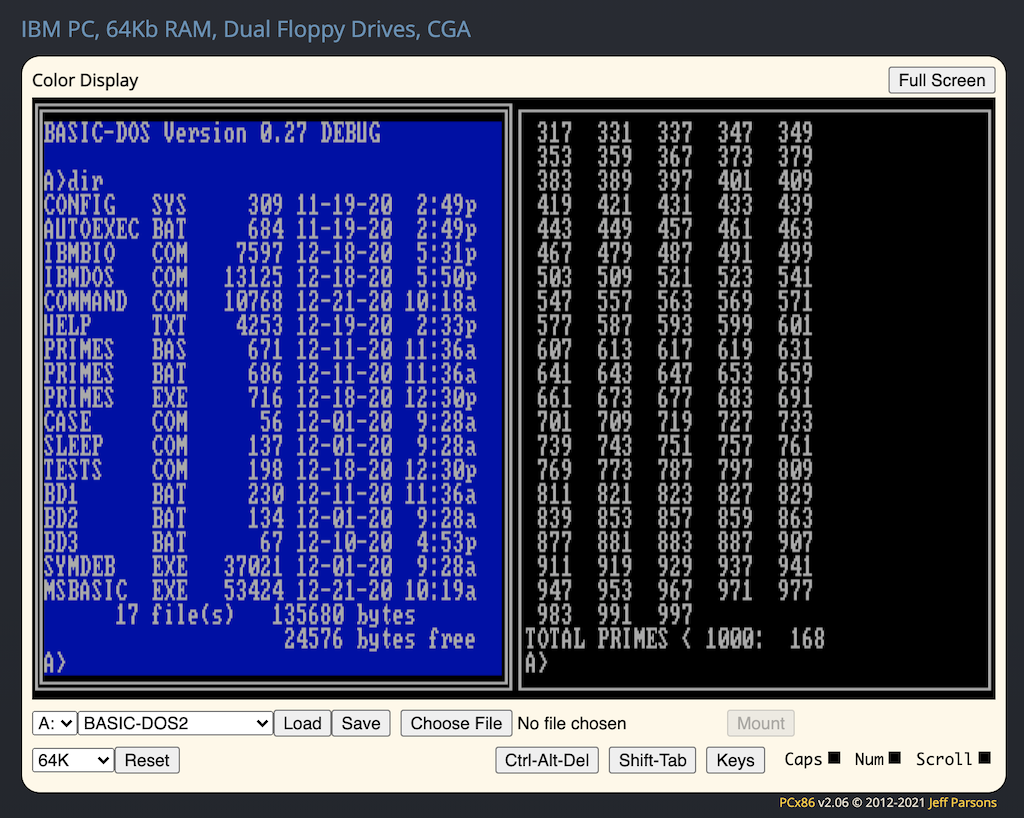

define two 40-column, 25-line sessions that are displayed side-by-side on an 80-column IBM PC monitor, each running their own copy of COMMAND.COM.

Sessions define a context within which one or more DOS programs may run, and the system automatically multitasks between sessions, providing the benefits a multitasking operating system while also supporting the traditional DOS application model.

At the moment, the Console driver is fairly dumb – it will create contexts with any size and position, without regard for other contexts, so if you define two or more overlapping contexts, expect to see a mess on the screen.

Contexts are created by opening the “CON” device with a descriptor, which is a string following the device name and colon; eg:

CON:40,25,40,0,1,0

The 6 possible values in a Console descriptor are:

- number of columns

- number of rows

- starting column

- starting row

- border style (0 for none)

- adapter number (0 for default)

Context borders exist within the context, which reduces the effective number of rows and columns by 2. Borders provide a visual delineation of the context, and the width of the border indicates which context has focus (ie, where keys will be delivered). However, they obviously come at the expense of valuable screen real estate.

The adapter number specifies which monitor to use in a dual-monitor machine. Adapter 0 is the default adapter (ie, the monitor the machine is configured to use on boot).

For example:

CONSOLE=CON:80,25,0,0,0,0

CONSOLE=CON:80,25,0,0,0,1

defines two full-screen border-less contexts, each assigned to a different monitor. In this case, the presence of a blinking cursor is your sole visual cue as to which context has focus.

The Serial Driver (eg, COM1)

For each serial device present in the machine, an instance of the COM driver will be installed. You can open a COM device with just the bare name (“COM1”), or with a basic descriptor (“COM1:9600,N,8,1”) to initialize the device, or with a full descriptor (“COM1:9600,N,8,1,64,128”) to also enable buffered asynchronous I/O (eg, a 64-byte input buffer and a 128-byte output buffer).

The Floppy Drive Controller Driver (FDC$)

This is a block device driver specifically designed for the IBM PC’s floppy drive controller. However, unlike the Console and Serial drivers, it does not currently support asynchronous I/O. I didn’t feel like taking on that work, so it’s largely just a wrapper for the BIOS INT 13h READ and WRITE functions.

Because it relies entirely on the BIOS, it needs the DOS kernel to “lock” the session while any disk operation is in progress, so that there’s no risk of a context-switch in the middle of a disk operation. That obviously isn’t ideal, but again, it saves a lot of work.

However, the FDC driver does more than simply wrap INT 13h calls. It improves on the BIOS interfaces by supporting:

- Partial sector requests

- Multi-sector requests

- Sector requests that cross 64K boundaries

Partial sector requests relieve DOS from blocking/deblocking I/O requests using intermediate buffers. So if an app wants just 10 bytes out of the middle of a sector, that request can more or less go straight to the FDC driver. And since the driver does its own buffering, such requests can usually be satisfied without hitting the disk again.

The BIOS supports multi-sector requests only as long as all the sectors are on the same track; the FDC driver eliminates that requirement, by breaking the request into multiple BIOS requests as appropriate. Multi-sector requests can even include partial sector requests, starting and/or stopping on non-sector boundaries.

And finally, while the BIOS could fail a request simply because the transfer address crossed a 64K boundary, the FDC driver automatically detects and avoids such failures.

There’s no support in the system for hard errors (eg, the familiar “Abort, Retry, Ignore” prompts). Any error, recoverable or otherwise, is reported immediately back to the caller. That’ll change at some point – probably after I add support to the Console driver for “popup” and background display contexts.

BIOS Parameter Blocks (BPBs)

While the BIOS Parameter Block (BPB) is a diskette structure that wasn’t introduced until PC DOS 2.00, it seemed like an important feature to include in BASIC-DOS.

BPBs on BASIC-DOS diskettes have a few additional fields that relieve the boot code from making unnecessary calculations (eg, the locations of the first root directory and data sectors), and when they are loaded into memory, they become Extended BPBs.

Every drive is assigned an Extended BPB, which eliminates the need for other data structures, such as Drive Parameter Blocks (DPBs) found in later versions of PC DOS, and the FDC driver supports MEDIA CHECK and BUILD BPB operations similar to those that PC DOS eventually supported.

BPB support means that BASIC-DOS can read any standard PC diskette, as long as the BIOS can read it. However, diskettes with subdirectories won’t be fully usable, at least not until the day comes – if ever – that BASIC-DOS supports them.

The DOS Operating System (IBMDOS.COM)

IBMDOS.COM is the second file loaded by the boot code. It installs handlers for all the usual INT 2xh software interrupts, the INT 30h vector for the old “CALL 5” CP/M-style interface, and the INT 32h vector for a new set of BASIC-DOS “utility” functions.

It supports a 12-bit FAT file system, and file operations can be performed with either FCB-style functions or the handle-based functions introduced in PC DOS 2.00. However, not all planned functions have been implemented yet. In particular, no write operations are supported, so BASIC-DOS effectively provides a read-only file system. This will change in the coming months.

The memory management architecture introduced in PC DOS 2.00 has been adopted by BASIC-DOS, with one significant difference: when a program is loaded, it is not allocated all available memory. It is provided with an ample stack, so that BASIC-DOS never has to switch stacks, but if the program wants more memory, it must explicitly allocate it.

Memory allocations are not partitioned in any way. Every allocation, regardless of which program or session requests it, comes from the same global memory pool.

EXE files can specify a minimum load-time memory allocation, which BASIC-DOS will try to honor. Even COM files can request additional “heap” memory at load time by appending a special structure and a BASIC-DOS heap signature (“BD”) to the end of the file.

Utility functions are loosely organized into a few major groups:

- string operations

- session operations

- miscellaneous operations

String operations include string-to-integer and integer-to-string conversions; length, search, and tokenization operations; and full-featured C-style printf and sprintf functions. These relieve the interpreter and every BASIC-DOS utility from having to duplicate the same functionality. They do come at the cost of an increased memory footprint, but the hope is that the benefits will outweigh the cost.

Session operations provide the ability to start and stop sessions, wait for sessions to complete, as well as traditional multitasking functions such as yield, sleep, wait, etc. Also note that CTRL-ALT-DEL is intercepted by the Console driver and transformed into a session “hot key” notification; BASIC-DOS will attempt to terminate the current program in the session with focus.

Miscellaneous operations include date/time manipulation functions, editing functions, object enumeration functions, and more.

The Interpreter (COMMAND.COM)

COMMAND.COM is intended to be a unified DOS/BASIC command interpreter that eliminates the need for a special “batch language”, “environment variables”, etc.

There’s no hard-coded support for an AUTOEXEC.BAT, but it’s easily added with a single line to CONFIG.SYS:

SHELL=COMMAND.COM AUTOEXEC.BAT

No special switches are required (eg, /P or /K). Each copy of COMMAND.COM loaded during the system initialization (aka “SYSINIT”) phase remains permanently loaded. Unlike PC DOS, COMMAND.COM is not divided into “resident” and “transient” sections. Instead, it’s divided into “shared” and “instance” sections, so every copy of COMMAND.COM shares the same code and read-only data, making each additional copy’s footprint much smaller.

At the command prompt, you can launch DOS and BASIC programs, and type a variety of DOS and BASIC commands. You can define your own variables and functions, print expressions, and even access some predefined variables, such as MAXINT and ERRORLEVEL.

There’s also limited support for pipe (|) and redirection (>) operations.

For example:

TYPE PRIMES.BAS | CASE

will “pipe” the output of the TYPE command to CASE.COM, a simple BASIC-DOS

I/O filter program that upper-cases all input. And in BASIC-DOS, these commands

are running simultaneously, as separate sessions sharing the same console and

file handles.

PC DOS didn’t support pipe operations version 2.00, and even then, pipes were simulated with temporary files, requiring a writable disk with enough free space to hold all the piped output, and the filters ran sequentially.

BASIC-DOS is free of those limitations. No disk operations are required, the pipe filters run in parallel, and the amount of piped data can be unlimited.

See the HELP command for a list of commands implemented so far.

To Be Continued…

In the meantime, check out the Preview, which highlights a few of our original Demos.

Jeff Parsons

Dec 12, 2020

Copyright (c) 2020-2021 Jeff Parsons Released under MIT License